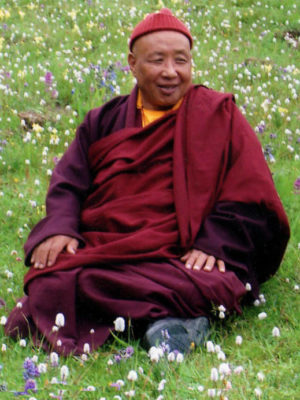

Welcome and introductory remarks at Lama Norlha Rinpoche Memorial Service

Kagyu Thubten Choling Monastery, Sunday, March 25, 2018, 2:00-4:30pm

Lama Yeshe Chodron, emcee

We’d like to warmly welcome all of you who are here today to remember Lama Norlha Rinpoche and to celebrate his life and his many accomplishments for the benefit of beings. I know some of you have traveled a long way to be with us for this day, and whether you’ve come from far or near, we appreciate your presence and this opportunity to be together as a sangha and family.

I’d like to begin by remembering what it took for Lama Norlha Rinpoche to be with us at all. The hardships he endured during the destruction of his homeland in the late 1950s, and his escape to Nepal in 1960, are almost unimaginable for most of us who have not personally experienced war and genocide, in our own country, in our own lifetime. Rinpoche often remarked on how lucky we are to live in a country, where personal freedom and freedom of religion are taken for granted, even with all its problems and imperfections. It was a very happy day when he became an American citizen in 1989.

Before his escape from Tibet at age 22, Rinpoche completed two three-year retreats under the guidance of his root lama Tarjay Gyamtso. He later expressed how grateful he was for the retreats, which helped prepare his mind for the extreme hardships ahead. Many of us have heard stories from Rinpoche, and from other lamas, of the six months Rinpoche spent in a prison camp and his nearly miraculous escape. He had already had to part from his elderly root lama, who had advised him when the armies arrived in Nangchen to flee with his family to a region of Tibet that had not been invaded yet. Rinpoche and his family managed to evade the slaughter that befell his hometown, but he was captured some time later and separated from his family. So when he finally fled Tibet, he was leaving not only his homeland but also everyone he loved and had known all his life. In fact, a dream he had the night before he was captured, foretold that painful separation: he dreamt that a huge yak impaled him with his horn, almost killing him, and then threw him high in the air, very far. He landed in a strange place, in some other country, with peaked roofs. He knew he was no longer in Tibet; and that he was all alone.

During their captivity, the lamas endured severe abuse, such as hard labor with meager food, being forced to use the same pot for cooking and toilet needs, and being trampled by guards wearing military boots, when they were lying down.

Every night, Lama Norlha Rinpoche’s root lama, Tarjay Gyamtso, would appear to him in his mind, just as if meeting face to face, and give him advice and tell him not to worry. That is when Rinpoche realized that he was never separate from his lama. Rinpoche was always looking for a chance to escape, and had slowly and cautiously come to trust four other lamas who wanted to join him, including Lama Namse Rinpoche, whom some of you may have met. To prepare for their escape, Rinpoche began hiding a small amount of his sparse portion of tsampa, or roasted ground barley, every day. He had found a discarded pair of pants, cut off the legs, and sewn them into the long sleeves of his traditional chuba coat, creating secret compartments to stash away some sustenance for the journey. The prisoners were subjected to daily searches, but luckily this cache of food was never discovered.

Each of the other lamas would also manage to smuggle something out to contribute.

On the night of their escape, Rinpoche had a dream that his lama told him that the time had come, and they must go right now. His lama appeared as a dharma protector and said he would cover the eyes of the guards. The moon was full that night, so when Rinpoche told the four other lamas, they were nervous, and wanted to wait for the new moon. Rinpoche told them he was sure now was the time, and that he would go first, and they all resolved to follow him. Even though there were guards posted about 30 feet apart, the lamas walked between them, straight out of the camp to their freedom.

It took them a year to reach Nepal on foot, in a very cold climate, kept alive by whatever food they could find, always in danger of being discovered and imprisoned again or killed.

Rinpoche’s life was also not easy as a new refugee in Nepal and India. A Hindu teacher, Neem Karoli Baba who also became the guru of Lama Surya Das and Krishna Das, found him one day living in an abandoned shack infested with snakes, and invited him to his ashram to live. They became close friends and Rinpoche stayed there until he was summoned a year later by Dorje Chang Kalu Rinpoche, his second root lama, for whom Lama Norlha Rinpoche now set up, led and sustained the first Kagyu three-year retreat in India, on the top of a mountain in Tsopema. He not only taught the retreats, but several times a week he climbed down the mountain to beg for food, often receiving 60 pounds or more of rice, water, and oil, which he then carried on his back all the way back up the mountain to the retreat—a three-hour climb. Despite the difficulty and fatigue, his only thought was how lucky he was to have such an opportunity to serve others in the dharma.

In 1976, Kalu Rinpoche and His Holiness the 16th Karmapa asked Lama Norlha Rinpoche to travel to New York City to direct the center Kalu Rinpoche had founded there two years earlier, Kagyu Dzamling Kunchab. He had, of course, never encountered an airplane before, and he said he recited a lot of mantras, certain that it would crash, because what could possibly hold this heavy iron bird up in the sky for such a long journey?

When he arrived in New York City at the age of 38, he had no money, and spoke no English. He knew very little about the West and had never been in such an urban environment before; and the students who greeted him also had little money, few material resources, and not much experience with the kinds of practical skills needed to construct buildings, sew brocades, and do all the other things that had to be done to fulfill Rinpoche’s vision.

From this beginning, over the next 40 years – exactly half of his life – he would build a pioneering Tibetan Buddhist monastery in the West, and establish the first three-year retreat program in the Americas; still going strong in its ninth cycle 36 years later. He would also fulfill Kalu Rinpoche’s wish for an enlightenment stupa to be built here. I vividly remember the obstacles to that accomplishment, beginning with endless planning board and zoning board meetings in the mid-1990s, with many questions about this strange proposed tall Buddhist concrete memorial. It took several years just to obtain approval for construction of the stupa, but Rinpoche was never daunted, and the stupa was finally completed in 2003.

His last great accomplishment also took years to complete. He was absolutely determined to get the Maitreya Center built, as an offering to Guru Vajradhara Chamgon Kenting Tai Situpa – Situ Rinpoche – under whose care we are now very fortunate to be. He overcame every obstacle, and every hesitation on the part of his students, and brought the Maitreya Center to final fruition just in time for KTC to host the 2016 North American Kagyu Monlam, a traditional five-day Kagyu prayer festival attended by hundreds of people, which brought immeasurable blessings to our corner of New York and to the United States and the world. We tried to convince Rinpoche that it would be more feasible to wait until 2018, the next time it would be hosted in the U.S. But with his vast vision he knew better, and insisted we must be ready by July 2016. And once again, he made it so.

During the 1990s and 2000s, he also established twenty or more dharma centers affiliated with KTC, from Maine to Peru, working with interested students to create environments where the Kagyu dharma could be shared and flourish under his personal guidance. He traveled to teach at these centers as often as he could throughout the 1990s and 2000s – to Bard College, to Richmond VA, to Boston, to Florida, to Washington DC, to New Hampshire, to Maine, to Tennessee, to North Carolina, to Peru – until he finally became too ill to travel in recent years. He also engaged in a great deal of dharma activity on his home continent of Asia, including several trips back to Tibet, where in the 1990s, he established many schools and medical clinics in remote areas of his native Nangchen. He also rebuilt Korche monastery, where he had trained and which was destroyed in the invasion of Tibet; and established a monastery for nuns at the holy site of Kala Rongo, where he also founded the first monastic college for women, who traditionally had few opportunities for dharma practice in Tibet. He took students on pilgrimages to India and Nepal several times, and made many visits to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China.

Rinpoche always seemed happiest when he was engaged in manual labor, always working alongside his students, harder than anyone, to construct buildings, chop wood, haul rocks, and so forth. He was particularly joyful when he managed to get his hands on a jackhammer as we dug out basements under the two retreat houses before the fourth retreat. He also loved to visit Shoprite to select the best ingredients for cooking, which he did often and with great enthusiasm. He always made sure to visit the seafood section to bless the live lobsters while he was there. His dal and momos were legendary, and many a Western student got their first taste of bitter melon at Rinpoche’s hands.

Through Lama Norlha Rinpoche we were extremely fortunate to meet many great teachers of the Kagyu and other Tibetan lineages: the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Gyalwang Karmapas; Dorje Chang Kalu Rinpoche of course; Chamgon Tai Situ Rinpoche; Jamgon Kongtrul the Third, whose untimely death in 1992 was so tragic; Gyaltsap Rinpoche; Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche; Sangye Tenzin Rinpoche; Mingyur Rinpoche; His Holiness Sakya Trichen Rinpoche; Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, and others. His Holiness the Dalai Lama visited KTC twice, in 1982 and 1997.

Aside from these visits, Rinpoche rarely had other Tibetans to talk with, and even more rarely other lamas. He spent the vast majority of his time surrounded by his Western students, whom he tirelessly showered with teachings, blessings, and his generous presence. He was so accessible to us, compared with most other lamas. For many years, until age finally began to take a toll on his energy, he chanted morning and evening services with us every day, as well as a daily Chenrezig practice. He also spent time regularly in the first few three-year retreats, personally teaching every practice and training retreatants in all the rituals of the Kagyu lineage down to the most basic tasks needed to support them. He ate three meals a day with us in the dining room until the last decade or so; and after that, he was still there for almost every lunch. Even as his illness progressed, he joined us in the dining room whenever he was able. He kept a humble profile in the West, even though in India and especially in Tibet he was highly revered, and he is credited by Kagyu lineage masters for helping to preserve the lineage through challenging times.

Even as KTC continued to expand and renovate, Rinpoche never used any of the offerings he received to enrich himself. He always wore simple robes and lived in a small, simple room. For many years he refused to let us make any improvements to his living quarters, though we begged him, for example, to let us replace the worn carpet. Eventually we realized that if we wanted to make his room nicer, the only way to do it would be when he was out of the country. His students also wanted to raise funds to build him a retreat cabin so he could occasionally take a break and devote himself entirely to practice, which he often said was what he would do if he didn’t have so many commitments. He always refused, preferring to use all available funds for KTC and not himself.

In the last two decades of his life, he experienced much illness, including two major, life-threatening surgeries and several emergencies. The pulmonary fibrosis that eventually ended his life caused a progressive decline in his health for several years, and the last few months required intensive round the clock care by several attendants. This illness causes increasing pain and difficulty breathing, yet Rinpoche remained cheerful and positive. Among his last words, when asked how he was feeling, he replied: “I am very happy. Because of the Buddha’s blessing, this feels like Dewachen. We are so lucky, we are all together, very nice.”

One evening in October 1980 when my friend Carolyn Hoberman and I had recently moved to New York City, Carolyn invited me to meet this Tibetan lama she had decided to study with after visiting several centers, and I went with her to the Wednesday night practice at Kagyu Dzamling Kunchab on West 19th Street, in a ramshackle fifth-floor walk-up loft, where I was introduced to the chanting practice of Chenrezig. Afterward, Lama Norlha gave a short talk on impermanence, with Gary Washington translating Rinpoche’s English into English the rest of us could understand. In those days, no one could speak Tibetan yet, so Rinpoche had to work within the confines of his very limited English, which was still amazingly effective. His teaching on impermanence really resonated with me because I had just broken up with my boyfriend. I remember him saying that when something comes to an end, no matter how long it lasted, it seems like it was over in a fingersnap. So true! Carolyn requested an interview for us, and Rinpoche kindly took us aside and asked if we had any questions. I was a bit overwhelmed and couldn’t think of anything to ask. Carolyn asked, what is the best way to deal with fear? Rinpoche immediately responded, “No matter what happens, think that everything is just like TV.” I still count that among the most helpful teachings I’ve ever received. I took refuge that week and almost 40 years later, it continues to transform my life. I will never forget Lama Norlha Rinpoche’s kindness to me, and I hope to meet him again and again until finally I can begin to approximate his vast kindness, compassion, generosity, and realization.

Lama Norlha Rinpoche’s second root lama, Dorje Chang Kalu Rinpoche, gave a teaching shortly before his own parinirvana in 1989, called “The Lama’s Mind is Like the Sky.” He said, “The essence of the lama or buddha is emptiness; their nature clarity; their appearance the play of unimpeded awareness. Apart from that, they have no real, material form, shape, or color whatsoever – like the empty luminosity of space. When we know them to be like that, we can develop faith, merge our minds with theirs, and let our minds rest peacefully. This attitude and practice are extremely important.”